History by design: Town halls, building a heart for the community

City Hall, or Village Hall, is more than a place to pay your water bill. It is the pulse of a community.

The city hall as a building type had its origins in the 12th century, when Europe’s feudal order was collapsing and control of towns was passing from royalty and the church to urban inhabitants — aka, the people.

Neither Highland Park (incorporated 1869) nor Kenilworth (incorporated 1896) had distinguished buildings symbolic of local government at the time their current halls were built.

Highland Park’s City Hall, 1707 St. Johns Ave., was first planned in 1923, when the city was growing exponentially. The population greatly increased, as did demands on city government, which was then housed in a small building at the corner of Green Bay Road and Central Avenue.

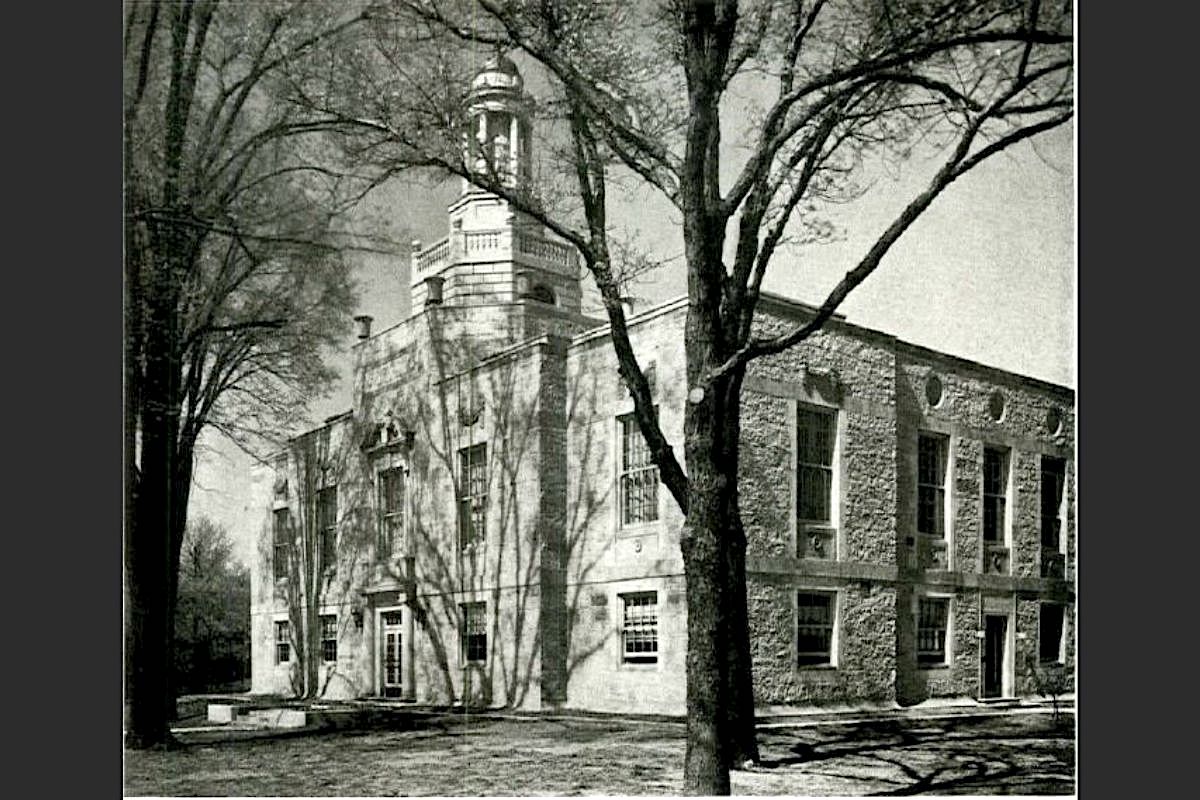

The cornerstone for an impressive city hall building was laid in August 1929. Completed in 1930, it was published in Architectural Forum magazine in 1931.

The new building was a prominent Georgian structure built of rough-faced limestone, giving it a venerable appearance. It was meant to suggest town halls of stone in early New England. Classicism dominated the simple rectangular form. Its front entrance was flanked by columns; the second-story window lighting the council chamber was topped by a broken pediment supported by brackets.

Crowning the building is a cupola (a small dome). The dome has historically been a characteristic feature of large civic buildings: capitols, courthouses and city halls. Beneath the cupola, on the first floor, is a rotunda.

The architect for the building was Frederick Hodgdon, a resident of Highland Park. Before forming his own firm, Hodgdon worked for his father, Charles, at Coolidge & Hodgdon. During the time that Frederick Hodgdon was with the firm, Coolidge & Hodgdon designed more than 20 buildings at the University of Chicago.

The Kenilworth Village Hall, 415 Kenilworth Ave., is unique, having been erected to house the Kenilworth Historical Society, which was badly in need of gallery and storage space.

Built in 1972 as the Stuart Memorial Building, the structure was financed by the estate of investment banker Harold Stuart. It was envisioned as a new civic center, with space leased out as a village hall, containing a boardroom, village offices and a police department. Village services had formerly been located in a grocery store, torn down when the Village Hall was built.

The Kenilworth Village Hall is also architecturally unique. Unlike most city halls, it is not meant to be imposing. The building is low and modest in scale, fitting for a community that values its fine residential character.

The architect was Philip B. Maher, son of Kenilworth architect George W. Maher. The building’s design was influenced by a museum Philip Maher had proposed for the 1933 Century of Progress. It is a minimalist single-story dressed limestone structure located in a park-like setting, with urns and benches, directly across the street from George Maher’s Kenilworth Assembly Hall. The Historical Society/Village Hall serves as a modern counterpart to the 1907 prairie-style Assembly Hall building.

Like his father, Philip Maher had a distinguished career. His work includes the Woman’s Athletic Club on North Michigan Avenue and the Art Deco high-rise apartment buildings at 1260 and 1301 N. Astor St.

The Village Hall building’s contractor, Bulley and Andrews, established in 1892, was an equally important Chicago firm. Allen Bulley, grandson of the founder, was a Kenilworth resident.

The Record is a nonprofit, nonpartisan community newsroom that relies on reader support to fuel its independent local journalism.

Become a member of The Record to fund responsible news coverage for your community.

Already a member? You can make a tax-deductible donation at any time.