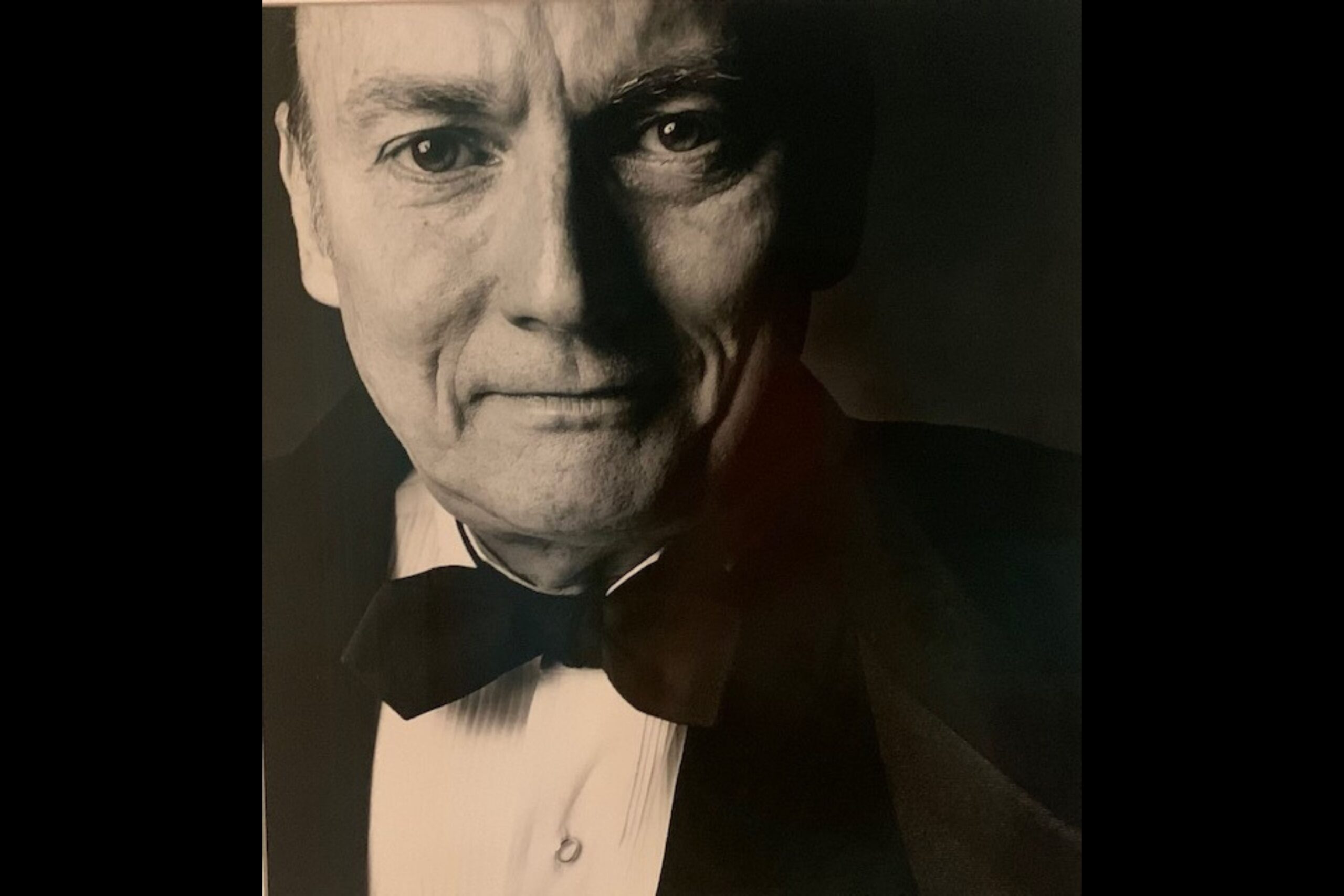

In Tribute: Kenilworth’s Alan Swain leaves incomparable legacy in field of jazz piano

The warm wishes and memorial notes arrived from all over in response to the death of Alan Swain.

Yet from the diverse group of senders, a common theme emerged.

“The most remarkable aspect of Alan Swain’s influence on the world of jazz is how similar everyone’s comments seem to be,” wrote Steve Sulkin, a longtime student of Swain’s. “Whenever you ask about Alan, people say, ‘He forever changed my life.’”

Sulkin is one of many mourning the loss of Alan Swain, a Kenilworth resident and jazz piano giant who died on Feb. 1 at the age of 94.

Swain is survived by his wife, Jennifer; daughters Janalee and Alana; and nephew, Kelly Alworth. Jennifer Swain said family is planning a celebration of life for the spring and will provide further information once details are finalized. In lieu of flowers, the family asks donations be made in Alan Swain’s name to the Jazz Institute of Chicago or Vitas Healthcare.

Alan Swain was unparalleled in his field. He founded and, for nearly 30 years, led the jazz studies program at DePaul University and quite literally wrote the book on jazz theory. Swain authored seven books between 1969 and 1984, including “Improvise: A Step-by-Step Approach” and the “Four-Way Keyboard System” series (I-III).

Swain made it his life’s work to teach, impacting the lives of hundreds of students, including many professional musicians, since he opened his teaching studio in the 1960s.

“Alan was just a person who changed lives,” said Jennifer Swain, Alan’s wife of 50 years. “He had people come to realize their goals of being musicians at whatever level they wanted. … Alan had a way of individualizing each lesson so a person could achieve their dreams and goals.”

Alan Swain grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and thrived as a jazz pianist, performing professionally by the age of 14. He graduated from the University of Tulsa with a degree in music before traveling to Chicago in the 1940s to attend graduate school at Northwestern University and break into the city’s jazz scene.

During his early Chicago years, Swain was drafted by the U.S. Army and served two years in Germany during the Korean War. He continued to play during his service.

When he came home, Swain returned to his craft, primarily with a jazz trio playing clubs and private events. But when someone asked him how he played “like that,” Swain’s perspective changed, Jennifer Swain said.

“He found out that he was super intrigued in that question. He found it very interesting,” she said. “He was a super intellectual and intense guy and thought, ‘How can I help people sound like this?’”

Alan kept playing until the 1980s, but he made it his business for 40-plus years to cultivate the future of jazz piano. Because of his personal instruction and his books, the “Swain methods” became an iconic term in the field.

Though Alan is no longer with us, he will live on through his students, his student’s students, and on and on, forever.”

Steve Sulkin, former student of Alan Swain

Alan developed one of the country’s largest piano studios.

“He was just one of these people who are unforgettable,” Jennifer Swain said. “I have heard from so many former students who are pros now that said, ‘No one could have taught me what Alan did.'”

And she would know. Jennifer is included on Alan’s extensive roster of students.

The two met while Alan was a graduate student at Northwestern. Years later, a friend of Jennifer’s showed her Alan’s first book, and a budding musician, Jennifer signed up to take classes with Alan out of his Evanston studio. The two married in March of 1972.

Her new last name created quite the buzz when Jennifer Swain performed. Audience members would often ask if she knew “The” Alan Swain. One night, while playing a private party, Jennifer Swain bet her bass player that someone would recognize her last name and ask about Alan.

“It happened three times at that job,” she said.

The couple had two children, Janalee and Alana, and moved to Kenilworth in the 1990s.

As the years passed, Alan became even more focused on music. He gave his final piano lesson when he was 91 years old.

Eric Lobo was one of Alan’s last students. Like many others, Lobo explained that Alan’s expertise and precision made him a better piano player, but Alan’s general depth and insight impacted Lobo’s life even further.

“Alan taught me to be fearless and that while I would never learn everything, that was the point,” Lobo wrote to The Record.

Lobo is now a piano instructor.

It is that impact that Sulkin said will allow Alan Swain’s legacy to endure infinitely.

“More than anything else, Alan inspired me,” Sulkin wrote. “Alan taught, not through lecturing, but by example. He taught me that life should be savored, that every moment counts.

“Because of Alan, I say what everyone says, ‘I’d have never had the life that I live today without Alan. I live because Alan lived.’ That’s Alan’s legacy and that’s why, though Alan is no longer with us, he will live on through his students, his student’s students, and on and on, forever.”

The Record is a nonprofit, nonpartisan community newsroom that relies on reader support to fuel its independent local journalism.

Subscribe to The Record to fund responsible news coverage for your community.

Already a subscriber? You can make a tax-deductible donation at any time.

Joe Coughlin

Joe Coughlin is a co-founder and the editor in chief of The Record. He leads investigative reporting and reports on anything else needed. Joe has been recognized for his investigative reporting and sports reporting, feature writing and photojournalism. Follow Joe on Twitter @joec2319